All good murder mysteries start with the discovery of a body. This one is no different, except this isn’t fiction and the crime took place one hundred and ten years ago. The body is that of a five-year-old child, strangled and hidden beneath the seat of a third class carriage on the 4.14 North London Chalk Farm to Broad Street train. Why would anyone want to murder a child? And why was no one convicted? These questions went unanswered at the time, and the crime remains unsolved.

I first came across the story of William Starchfield on the website of the British Transport Police.1 Intrigued, I searched for more information and found the original Metropolitan Police investigation files on the National Archives website. At the time, I was in my final year of a joint English Literature and History degree at the University of Liverpool. I should have been concentrating on finishing my dissertation, not looking up details on unsolved murders, but curious as to what I might discover, I submitted a page check request and eagerly awaited the email detailing the cost of a digital copy of the file’s contents.

Two weeks went by and with my attention firmly fixed on my assignment I’d almost forgotten about the page check. I was a little bit stunned at the price, but with freedom from assignments and deadlines just around the corner I wanted something that would fill the gap and give me a project on which to use the skills I’d been acquiring for the last few years. I hit the purchase button.

I’d never read a police file before and had no idea what to expect, so when I opened the files I was astonished to find a jumbled collection of typed and handwritten reports, scraps of paper, and newspaper clippings in no particular order. Each sheet had been allocated a number made up of the MEPO file (Metropolitan Police File) number followed by a sheet number in the order they had been scanned. So the first sheet in the file was Mepo 3_227B_01 followed by Mepo_3_227B _02 and so on. This was all well and good, but the individual sheets had not been scanned in chronological order which I had naively believed they would be. Thankfully, where statements had run over more than one page these were numbered consecutively, but my first task was to sift through the file, putting each item in date order.

There were 247 pages in the file, all of which I entered into a database with the date, MEPO file number, and a description of the content. Then I sorted each item into folders, starting with the day of the murder, 8th January 1914, as Day 1 and ending in July 1921. A total of 48 folders.

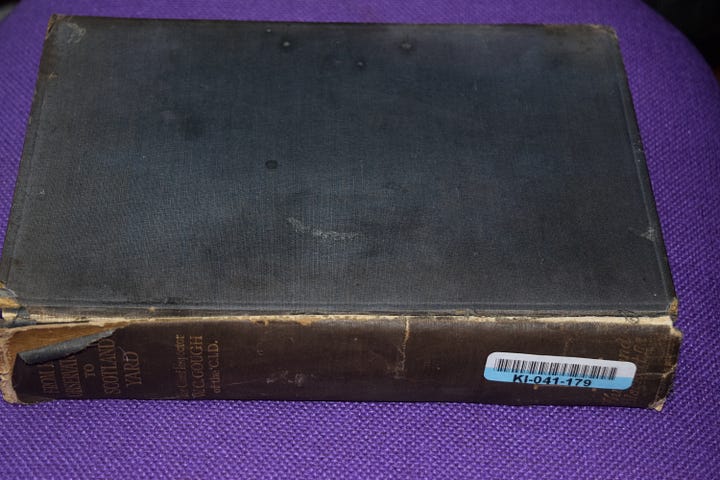

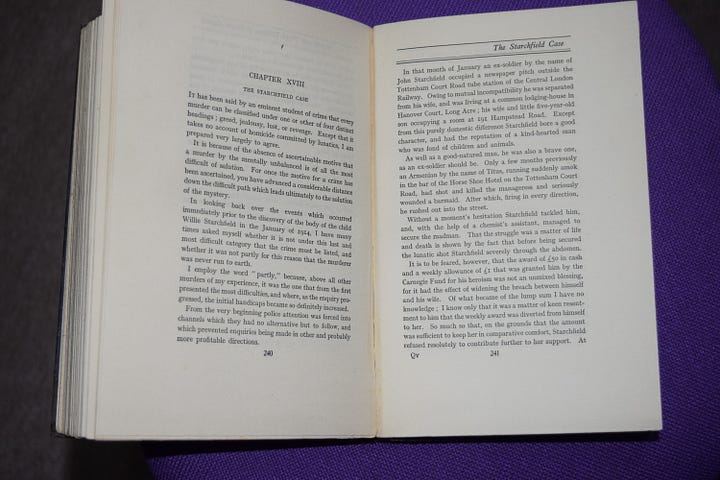

I made an annotated bibliography of any previous research I could find on the subject, mostly just a handful of books that included a chapter or brief description of the murder along with other railway and 20th century murders, but little in the way of detailed investigation. However, there was one interesting discovery. Detective Chief Inspector William Gough, the man who headed up the investigation into Willie’s murder, had written a memoir of some of the most infamous cases he worked on during his time as a member of Scotland Yard’s CID. Willie’s case was one of them, and I managed to find a rather dilapidated copy.

After reading his account, followed by the MEPO file itself, it became apparent that there was a great deal of information missing. Statements from key witnesses were completely absent. Perhaps they had been lost or filed elsewhere, but their absence left large holes in the investigation. Further searches through the archives turned up three more files that I hoped would fill in the gaps, but then Covid hit. The National Archives shut its doors and everything was put on hold.

Months later, as things started to open up again, the collective reluctance to travel long distances meant more people were doing their research online. The National Archives were overwhelmed with page check orders and limited the number they could do each day. Daily visits to the website revealed time and time again that orders for the day had reached their maximum with the message ‘Try again tomorrow’.

But gradually, normality returned, and in June 2023 my page check of CRIM 1 145/3 hit my inbox. I opened the email with my fingers crossed and then slumped when I saw the cost of a digital copy of the pages - almost £600! And that was just for the one file, there were still two others I needed.

I’d been saving up, but I couldn’t justify that kind of expense. I’d have to rethink everything. Having already invested so much time, effort and money into the project the idea of giving up and forgetting all about it was unimaginable.

I searched the newspaper archives on Findmypast.com, returning over 2500 articles on Willie’s family, the murder, the inquest, and trial, dating from 1907 to as late as 1958.4 Was it possible to fill in the gaps with information from contemporary newspapers?

I downloaded and catalogued each article in the same way I had for the MEPO file. The ones preceding the year of the murder were often as intriguing as the murder itself, but we’ll discuss those later. Many articles were simply word-for-word copies circulated by the news agencies of the time, but there were interviews with some of the missing witnesses, and photos, and occasionally, new or conflicting information would come to light. The first reports of Willie’s age and background were completely erroneous, which is one reason historians never take these sources at face value.

If I relied on the newspapers I would never be certain that the information was accurate, or that some crucial detail wasn’t still missing. There was only one way to be sure. I had to get copies of the other files, no matter what the cost or how long it took me.

And then a solution presented itself. I’ll tell you more about that in my next post.

1. Website of the British Transport Police, The Murder of Master Starchfield, 1914

2. The National Archives of the UK (TNA): MEPO 3/237B

3. The National Archives of the UK (TNA): CRIM 1/145/3

4. Find My Past Newspaper Archives https://www.findmypast.co.uk/