DCI Gough tells us about his involvement in what has become an enduring mystery. Was a young man murdered in cold blood for the proceeds of a life insurance policy, or was he the unfortunate victim of a tragic accident?

An old colleague of mine was in the habit of saying that the finest detectives in the world are “Inspector Luck” and " Sergeant Chance”. The truth of that shrewd aphorism is testified by the number of times in my own career that those two stout allies have come to my aid and enabled me to carry an apparently hopeless case to a successful conclusion.

In no instance of close upon thirty years of service as a detective was I so well served by these friends of justice than in what is known as the Ardlamont Mystery; indeed, had it not been for causes outside my own control, which went to negative the good offices of Inspector Luck and Sergeant Chance, it is more than possible the Ardlamont Mystery would have remained a mystery no longer.

In the year 1890 there was living in retirement a certain Major Hamborough, whose sole means of livelihood for some years had been derived from his interest upon property of which, because it was entailed for the benefit of his only son, he could not touch a penny of the capital.

Now the gallant major happened to be possessed of a certain devotion to the good things of this life, and, as interpreted by him, the good things of this life could not be purchased for the price of the revenue from the property. In plain words, he was desperately hard up, and completely at his wits end to obtain money to satisfy the creditors who at this time were pressing him unmercifully, or to provide the luxuries apart from which existence would have been intolerable. At the time of which I am writing, and because, on account of his failure to pay the interest, the insurance company with whom he had mortgaged his interest in the estate for £37,000 had foreclosed, and thus owned the life interest in the property in his stead, he was more desperately in need of money than usual. So far as he could perceive, his only chance of relief was to persuade his son Cecil to break the entail and so permit of a further substantial mortgage being raised on the estate. But, as this could not be done until the boy reached his majority, which would not be for another four years, there was not much immediate satisfaction in that.

Among Major Hamborough's acquaintances was a London moneylender named Tottenham, who knew an Army coach by the name of Monson, the latter of whom for a consideration of £300 a year consented to receive the boy Cecil into his house and to coach him for the Army. In due course Cecil Hamborough took up his residence with Captain Monson at Riseley Hall, in Yorkshire.

About that time it occurred to Tottenham that it would be no bad investment to purchase Major Hamborough's life interest in the estate from the insurance company. When it came to the point, however, he was unable to raise the money. So he enlisted the help of Monson.

Not that the Army coach had any money; he hadn't; the idea was to borrow it on the security of the estate he was endeavouring to purchase. There was big profit in the deal if it could be brought off. The mortgage was for £37,000, and if the boy Cecil would consent to break the entail the freehold alone could quite readily be sold for £135,000. Of this sum, after repaying the mortgage and legal expenses, there would remain no less than £89,000. The arrangement was that of this Cecil was to have £67,000 and the balance of £22,000 was to be divided equally between the Major and Monson, of which latter portion it is to be presumed Tottenham would have stood in for a share.

The only problem was that before the scheme could be consummated it was necessary first to effect a large insurance on the life of Major Hamborough. When he came to be examined, however, the medical report was such that no insurance company in the world would have taken the risk of issuing a policy. Thus the scheme, like those of other mice and men, fell through.

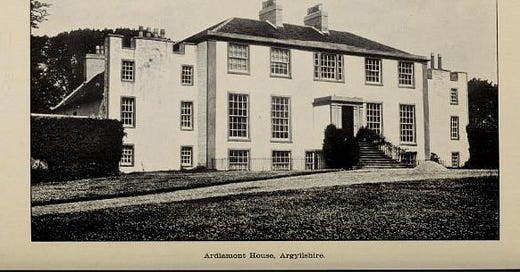

This state of deadlock continued until the year 1893, when Monson and Cecil Hamborough left Riseley Hall to take up their residence on a small estate in Argyllshire, named Ardlamont. Nominally the house and land, for which the rent was £450 a year, was taken out in the joint names of Cecil Hamborough––a minor without income––and a man named Jerningham, who appears to have been as penniless as Monson himself. Actually, of course, the leaseholder was Monson, whose name could not be allowed to appear in the transaction on account of him being bankrupt. To show the financial position of the tenant it is necessary only to state that he was obliged to borrow money from Tottenham to pay for the removal, and that he left his laundry behind because of financial inability to pay the bill. Food and necessities were obtained by the simple expedient of pawning Mrs. Monson's jewellery.

At this stage it may not be unprofitable to speculate as to what motive Monson could have had in leaving a comparatively populous neighbourhood like Riseley to migrate to the solitude of Ardlamont, where, in addition, the rent was half as much again as the fees he received for coaching.

It is possible that the solution may be found in what so shortly afterwards transpired in that lonely Argyllshire house. For they had been there only a few days when, on the plea that Cecil had agreed to buy Ardlamont at the bargain price of £45,000, Monson asked Tottenham for the loan of £250, a sum he said was demanded by the vendors in order to seal the bargain.

This statement was a lie from beginning to end. Cecil Hamborough never had the least intention of purchasing the property. Nevertheless, the lie came off, and Monson got his £250—money he required for an entirely different purpose.

He had persuaded his pupil to sign two proposal forms of £10,000 each with the Mutual Life Assurance Company of New York. And although it was necessary for the contract to be ratified in America, the state of Cecil Hamborough's health was so good that the Glasgow agent for the company had no hesitation in issuing a cover–note for sixty days in return for the payment of first annual premiums of something like £125 each.

It was immediately following the receipt of this document that Monson induced Cecil Hamborough to instruct the company that in the event of his death the money due was to be paid to Mrs. Monson. And because these instructions were invalid in law, very grave issues were afterwards to hang upon the answer to the simple question as to whether Monson was or was not aware of this at the time they were given.

The cover–notes were issued on the eighth of August, and simultaneously with their receipt another figure appeared at Ardlamont in the person of a mysterious gentleman who was described as an engineer come for the purpose of examining the boiler of a yacht which, by some means known only to himself, Monson had persuaded the owner to let him have on credit. Actually Scott, as he called himself, was a London bookmaker with several aliases, of which Davies and Sweeney were only two. It was following the appearance of this man, and upon whom such tragic issues were to depend, that things began to move.

In close proximity to Ardlamont was a loch in which there was very good fishing. But although Monson had hired a boat from a man named M'Kellar, as soon as Scott arrived, and on the grounds that the first was unsafe, he hired another from a man named McNicoll.

On the night of the next day Monson and Cecil Hamborough went out fishing in McNicoll's boat. Before they had been embarked very long the boat upset, and but that there happened to be a rock nearby to which he clung, there can be but little doubt that the boy would have been drowned. As it was, Monson swam to the bank, pushed off in another boat, and effected a rescue.

When, later, the first boat came to be examined, it was found that someone—exactly who was never discovered—had cut a hole in the bottom. At the time Monson accused the boy, but this the lad most strenuously denied.

It was, however, the following day that the real tragedy occurred, and very early in the morning at that.

Before breakfast, Monson and Cecil Hamborough went shooting in the woods near the house, and though Scott accompanied them he carried no gun. About seven o'clock Monson rushed back to the house, carrying his own and Cecil's gun, and, in an agitated voice announcing to the butler that Hamborough had shot himself, instructed him to fetch something on which the body could be carried to the house.

A rug was obtained, and, proceeding to the point indicated by Monson, the carrying party of outdoor servants found the boy, shot through the base of the skull, lying with his head in a pool of blood at the top of a sunken fence.

The body was taken to the house, and a local doctor by the name of Macmillan summoned, who pronounced death to have been instantaneous. To the medical man and others, Monson stated that at the time of the tragedy they had been after rabbits, for which purpose the little party had separated. Young Hamborough had followed the line of a dyke, with Scott walking parallel a little distance away, and himself taking a similar direction on the outside.

Hearing a shot, he had called :

“Have you got anything?”

No reply forthcoming, he had become alarmed, and crossed over to where the boy had been, only to find him dead.

Upon the doctor's enquiry as to whether the boy carried any insurance—an unusual question, one would think, at such an early stage—Monson returned an emphatic and lying negative. Whereupon, without apparent hesitation, Dr. Macmillan gave the necessary certificate to enable the remains to be interred.

Monson then telegraphed the news to Major Hamborough, who came at once to take charge of the body, which eventually was buried in the family grave at Ventnor, in the Isle of Wight.

In the meanwhile occurred what perhaps was the most significant event of all that had yet transpired. Scott, upon the evidence of whom such grave issues were to depend, disappeared.

The next move in the drama, and one which was the primary cause of a case that will go down in criminal records as one of the most extraordinary in the history of British trials, came from the moneylender, Tottenham.

With the knowledge and consent of Monson he sent in a claim to the Mutual Life Assurance Company of New York for £20,000, the amount of the two policies the cover-notes for which, it will be remembered, had been issued only two days before the death of the assured.

Under circumstances such as surrounded the case of Cecil Hamborough no life insurance company could recognise a claim without the most searching enquiries, and the two agents of the company who were sent to investigate were far from satisfied that the death was beyond suspicion. Actually they became so convinced of foul play, that they took the grave step of interviewing the Procurator-Fiscal, the representative of justice for the county, and on the facts as they conveyed them had little difficulty in infecting him with their own suspicions—so much so that he sent for Monson and put him through a searching cross-examination as to the exact details of the circumstances under which young Hamborough had met his death.

Monson came badly out of the ordeal. Convinced now that the case was one which in justice to all concerned demanded close investigation, the Procurator-Fiscal took immediate steps towards that very desirable end. An order was obtained from the Home Secretary for the exhumation of Cecil Hamborough's body, and two doctors despatched to Ventnor to superintend disinterment and afterwards make an examination of the body.

As a result of the examination a detailed statement was demanded, and obtained, from Dr. Macmillan—who, it will be remembered, was the medical man who supplied the death certificate—following which, warrants were issued for the arrest of both Monson and Scott, and the former was taken into custody. Scott, as already has been written, was not to be found.

It was appreciated at once that without the presence of the London bookmaker the trial of Monson would be very gravely prejudiced, and a hue and cry was sent out for his apprehension. It was while the search was at its height that my old friends Inspector Luck and Sergeant Chance came to my assistance. Would that their kindly efforts had been more fortunately seconded!

At that time I was but a junior in the C.I.D., and consequently without anything like the authority which afterwards I came to possess; certainly not sufficient to take independent action in an issue of such importance as the possible apprehension of the missing Scott.

During my Richmond days I used occasionally to play billiards at the famous old Greyhound Hotel there with man who, though fairly prosperous at that time, had subsequently got himself into the hands of moneylenders, and as an inevitable consequence had gone rapidly downhill.

Walking down Oxford Street one day, I came across this man in company with a somewhat shabby individual who bore all the earmarks of a bookmaker's runner, out-of-work billiards-marker, or moneylender's tout. Actually he was the latter, and not in a very good way of business at that.

With nothing more important in my mind than that an old acquaintance should not have cause to think I was too proud to speak to him, I stopped, with the idea of having a few casual words and then passing on. But almost the first remark he made after greetings had been exchanged caused me to determine that any time I spent with this pair of down-and-outs might prove more than a little profitable.

“We've been talking about that Ardlamont case,” remarked my billiards friend, and made a gesture with his thumb towards his companion. “This old sport knows something,” he added importantly.

Glancing at him quickly, I could see the man stiffen. Where before he had been effusively garrulous, now he became at once taciturn and uncommunicative, And from that moment I became convinced that he did indeed know something. By hook or by crook I determined to share that knowledge.

For a time, however, he would say nothing, protesting that his friend was wrong in suggesting he had any special knowledge of the Ardlamont case.

“Come and have a drink,” I said—an idea which appeared to commend itself to both.

Inside the wine-vaults I got really to work. I told the tout I was convinced that he knew more of the case than he appeared willing to admit, and that if he didn't speak he might find himself very unpleasantly situated. If, on the other hand, he was frank about what he knew, I promised him protection against any threat of harm which might come to him from his associates.

Eventually he gave way, but was too frightened to open his mouth there and then. And as, after all, the bar of a public-house is not a particularly favourable place for the exchange of confidences, I arranged to call upon him that same evening at his place of living at Twickenham.

Of course I kept the appointment, and neither did I go alone. I did not know what I was to hear, but, whatever it might be, there seemed more than a possibility that corroboration of the conversation might prove useful. So I took a colleague along with me.

The man had a tiny, ill-furnished house, and we were shown into an untidy room. Not that the surroundings mattered; provided I got what I wanted, it would have made no difference if the interview had been in a coal-shed. And I received information in that bare room which, but for circumstances outside my own control, would probably have been directly instrumental in breaking the dam which so seriously held up the springs of justice in the Ardlamont case.

The man did not know where Scott was. What he did know, however, was that Scott's brother was employed as porter in a London hotel, and in all probability would be posted as to the whereabouts of the man for whom the whole police force of the country were so vainly and feverishly in search.

Armed with this information, I hurried back to have it submitted to the senior officer in charge of the case––an enforced formality which lost us our man. It was not until some hours after the information had come into our hands that the hotel was called upon, and by that time the individual it was so necessary to interview was not on duty.

From the proprietor, however, we learnt the address of the porter, who was in lodgings in Pimlico. We learnt more than that; we discovered that actually he was sharing rooms with his brother—the missing Scott!

I had, then, in my possession, knowledge which the whole police force of the United Kingdom had been searching for weeks to obtain. And yet, though the information was accurate in every detail, it proved to be absolutely without value. For owing to delay occasioned by formalities it was the following morning before we were able to call at the address indicated by the hotel proprietor.

Scott had been there, but had left some few hours previously. Whether he had received a hint that the scent was getting warm I do not know. The fact remains that he had gone, and that in consequence Monson had to stand his trial alone.

The charges heard at the High Court of Justiciary in Edinburgh were against both Monson and Scott, and consisted of two distinct indictments; the first of attempting to murder Cecil Hamborough by drowning on the night of August the ninth; the second with the murder of Cecil Hamborough by shooting on the day following. In addition there was a special charge against Scott for absconding from justice. As he was not there to answer, he was outlawed with all the rigid ceremony of the Scottish High Court. To the charges against Monson the prisoner entered the formal plea of “Not guilty.”

The counsel engaged in the case represented the best of the Scottish Bar. For the Crown appeared the Solicitor General, Mr Asher, Q.C., with Mr Strachan, Mr Reid, and Mr Lorrimer as juniors; while Mr. Comrie Thomson, Mr. J. Wilson, and Mr. W. Findlay represented the “panel”—as a prisoner is called in Scotland.

Let me say at once that, with the possible exception of the late Marshal Hall's fight for the life of Bennett, the Yarmouth beach murderer, I have no recollection of a more brilliant defence than that urged by Comrie Thomson on behalf of Monson. He had a task of most exceptional difficulty, but his conduct of it was masterly. There was no single point either of favour or of doubt which he did not seize upon and urge to its fullest extent, or from which he did not extract the last ounce of capital. One advantage, moreover, which a Scottish advocate possesses over his English colleague is the verdict of “Not proven” which obtains in the Caledonian Courts, and by which a counsel who is unable definitely to prove the innocence of his client has a second line of defence in the question: “Are you quite certain, are you positive that in this case there is absolutely no shadow of doubt as to the guilt of the prisoner ?”

Of what advantage Comrie Thomson made of this very tangible asset the result of the trial bears most eloquent testimony.

The story will conclude in Part Two.